In the first part of this 2-part series, chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez looked at the likely signs and symptoms of disc Herniation, in addition to the selection standards for micro-discectomy surgery in athletes. In this report he discusses the lengthy rehab period following a micro-discectomy procedure, and provides a plethora of strength based exercises.

Surgeries to ease disc herniation, with or without nerve root compromise, comprise traditional open discectomy, micro-discectomy, percutaneous laser discectomy, percutaneous discectomy and micro- endoscopic discectomy (MED). Other surgical conditions are employed in The literature like herniotomy that’s interchangeable with fragmentectomy or sequestrectomy. The saying ‘herniotomy’ is defined as removal of the herniated disc fragment just, and the ‘standard discectomy’ as elimination of the herniated disc along with its degenerative nucleus in the intervertebral disc space.

When surgery is required, minimizing tissue disruption and strict adherence to an aggressive rehabilitation regimen may expedite an athlete’s return to perform(1), that explains why micro discectomy is a favored surgical procedure for athletes. Micro discectomy procedures entails Removing a small part of the vertebral bone over a nerve, or removing the fragmented disc stuff from under the compressed nerve root.

The surgeon can then enter the spine by removing the ligamentum flavum that insures the nerve roots. The nerve roots can be visualized with functioning eyeglasses or with an operating microscope. The surgeon will then move the nerve to your side and to subsequently remove the disc material from beneath the nerve root.

It’s also sometimes required to eliminate A small portion of the related facet joint to permit access into the nerve root, and additionally to relieve pressure on the nerve root resulting in the facet joint. This procedure is minimally invasive since the joints, muscles and ligaments are left intact, and the process doesn’t interfere with the mechanical construction of the spinal column.

Table of Contents

Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy

Local Doctor performs lumbar discectomy using minimally invasive techniques. From the El Paso, TX. Spine Center.

Surgical Outcomes

In general, athletes with lumbar disc Herniation have a favorable prognosis with traditional therapy; more than 90 percent of athletes using a disc herniation improve with non-operative treatment. Many demonstrate a response to conservative treatment with increased pain and sciatica within 6 weeks of the initial onset(2). This implies that the requirement to function immediately could be considered hasty.

However, in case of failed Conservative therapy, or together with the pressure of a significant upcoming competition, surgery might be needed in some instances. Even though it involves surgical therapy, micro-discectomy has been reported to have a high success rate — over 90 percent in some studies(3,4). Patients generally have hardly any pain, are able to return to preinjury activity levels, and therefore are subjectively happy with their results.

The achievement rate of micro-discectomy is The following studies have been summarised to underline the success rate of micro-discectomy procedures:

1. In a survey on 342 professional athletes Diagnosed with lumbar disc herniation in sports like hockey, football, basketball and baseball, it was discovered that powerful return to perform occurred 82% of this time, and 81 percent of surgically treated athletes returned for an additional average of 3.3 years(5).

2. From a limb paresis which might be associated with a disc herniation following surgical treatment. If the preoperative paresis was mild then they could anticipate an 84% likelihood of full recovery. Patients with more severe paresis have less chance of recovery (55%)(6).

3. Wang et al (1999) in a study on 14 athletes demanding discectomy processes found that in single degree disc procedures, the return to game was 90%. However when the procedure involved 2 levels enjoyed considerably less favorable results(7).

4. In a study of 137 National Football League players with lumbar disc herniation, surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation led to a significantly more career and greater return to play rate than those treated non-operatively(8).

5. Schroeder et al (2013) reported 85% RTP rates in 87 hockey players, with no substantial difference in outcomes or rates between the surgical and nonsurgical cohorts(9).

6. A study by Watkins et al (2003) coping with professional and Olympic athletes revealed the acceptable outcomes of micro-discectomy concerning return to play, since elite athletes in general were highly encouraged to return to perform(10). Also, athletes who had single-level micro- discectomy were more likely to come back to their original heights of sports activities than were people who’d two-level micro- discectomies.

7. A study by Anakwenze et al (2010) investigating open discectomy at National Basketball Association participants demonstrated that 75% of patients returned to perform again compared with 88 percent in control subjects who did not undergo the operation(11).

8. A recent review found that conservative therapy, or micro-discectomy, in athletes using lumbar disc herniation seemed to be satisfactory concerning returning the injured athletes into their initial levels of sports activities(12).

These studies conclude that though a Analysis of lumbar disc herniation has career-ending potential, most gamers have the ability to return to play and generate excellent performance-based outcomes, even if surgery is required.

What is also apparent from research Studies is the level of this disc herniation can also determine prognosis after surgery. Athletes shower a greater difference in progress between surgical and non-operative treatment for upper amount herniations (L2-L3 and L3-L4) compared to herniations at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels. Patients using the upper level herniations needed less progress with non-operative treatment and marginally better operative outcomes than those with lower degree herniations(13).

There are several possible explanations A range of studies have revealed that low spinal canal cross-sectional area is associated with an increased likelihood of symptomatic disc herniation, and increased intensity of herniation symptoms. The spinal cross-sectional region is the smallest (thus contains a larger possibility of nerve compromise) at the most upper posterior section and the cross-sectional region increases further down to the lower lumbar spine(14).

The location of the disc herniation (foraminal, posterolateral or central) may also contribute to differences. In this study, upper lumbar herniations were more likely to happen in the much lateral and foraminal positions than were people in the lower two intervertebral degrees(13).

Post-Surgical Rehab

After micro-discectomy surgery, the Small incision and restricted soft tissue injury makes it possible for the patient to be ambulatory reasonably fast, and they’re usually encouraged to start rehabilitation sooner or later during the 2-6 weeks after surgery.

In a review on the efficacy of busy Rehabilitation in patients following lumbar spine discectomy, it may be reasoned that individuals can safely take part in high or low-intensity supervised or home-based exercises initiated at 4 to 6 weeks following first-time lumbar discectomy(15).

Herbert et al (2010) discovered that with Effective post-surgical rehabilitation plans, there was a key accent on lumbar stabilisation exercises(16). Second, positive trials tended to initiate rehabilitation earlier in the postoperative interval compared to negative trials (about 4 vs 7 weeks).

Outcome Measures

The most widely used result Measure following back injury and/or disc surgery is the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire(17). This questionnaire is reported to have good levels of test-retest reliability, responsiveness, and also a minimum clinically important difference estimated as 6 percent(18) Furthermore, treatment success has been defined as a 50 percent decrease in the Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire score(19).

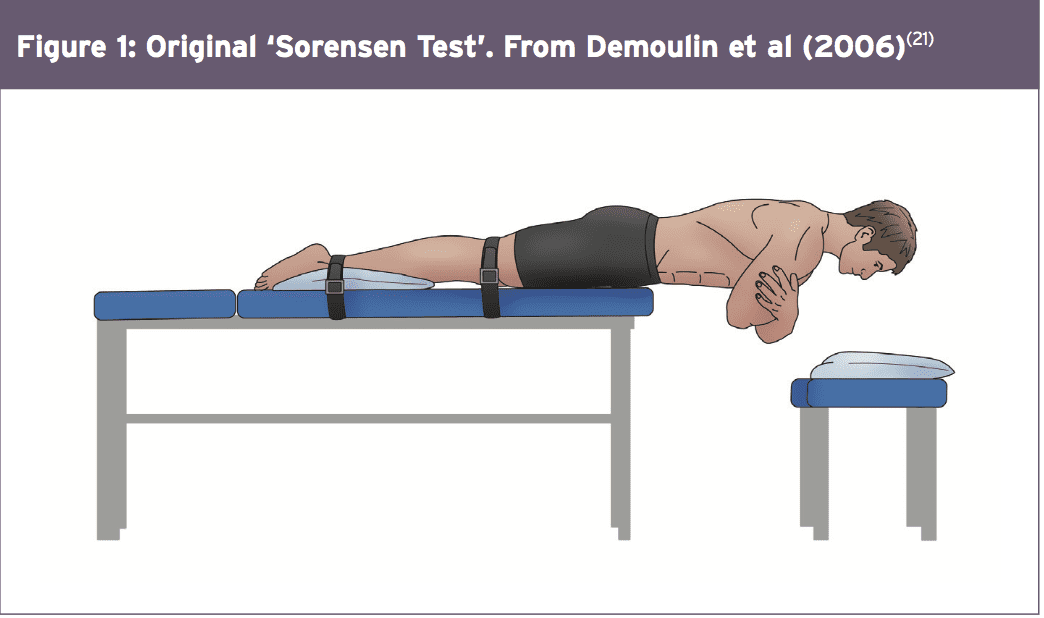

Concerning physical performance measures following back disc or pain operation, a commonly used clinical examination is that the Beiring-Sorensen Back Extension examination (see Figure 1)(20). This test is performed in a prone/horizontal body position with the spine and lower extremity joints at neutral position, arms crossed at the chest, lower extremities and pelvis supported with the top back unsupported against gravity.

Rehabilitation Program

Rehabilitation Program

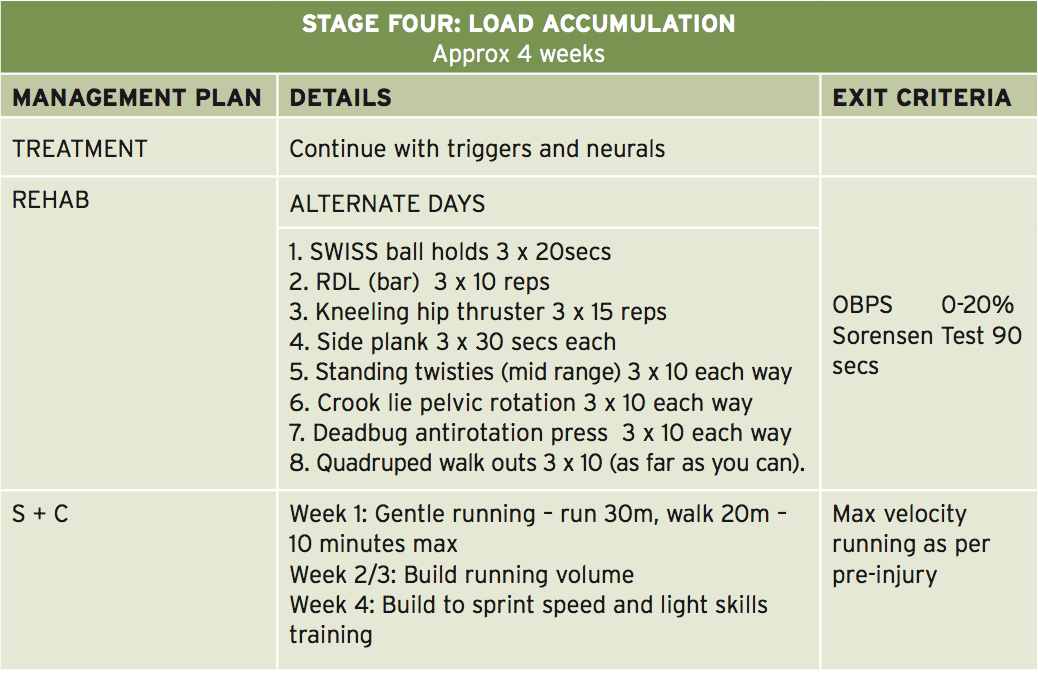

Presented below is a five-stage rehabilitation program. The stages involved in rehabilitation are:

1. Optimize tissue healing — protection and regeneration

2. Early loading and foundation

3. Progressive loading

4. Load buildup

5. Maximum load

This program has been designed to get a field hockey player with had a L5/S1 lumbar spine discectomy. Even though the progressions from one point to the next are driven by the exit standards related to that stage, it might be anticipated that the athlete could progress in post-surgery to ‘fit to compete’ in about 12-13 weeks.

The key features in each phase are as follows:

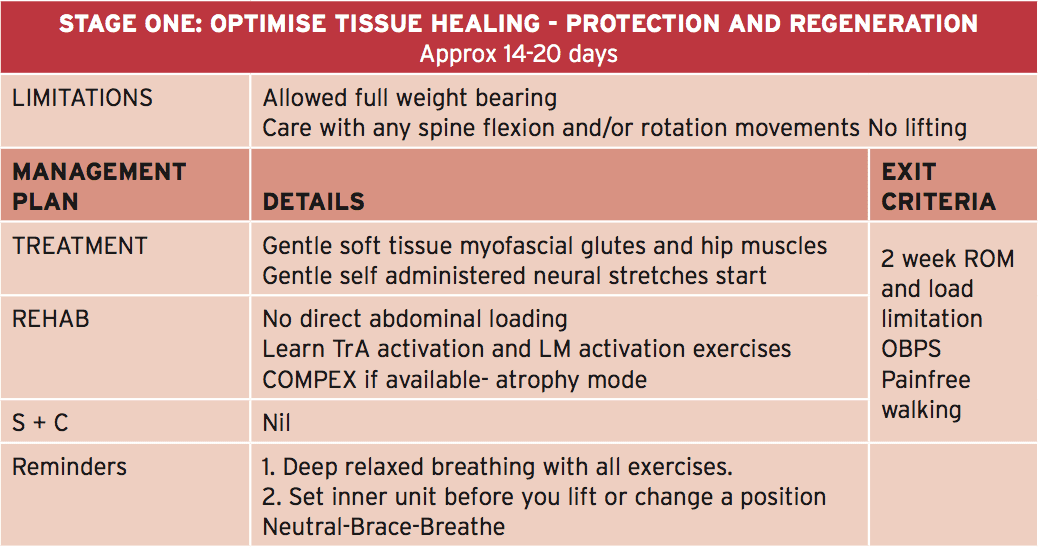

Optimise Tissue Healing — Protection & Regeneration

In this phase it’s anticipated that the athlete will remain relatively quiet for 2-3 weeks post surgery. This allows for full tissue recovery to happen, including scar tissue maturation. The athlete is allowed to completely mobilize in full weight-bearing; however care needs to be taken using any flexion and rotation motions and no lifting will be allowed.

In this phase it’s anticipated that the athlete will remain relatively quiet for 2-3 weeks post surgery. This allows for full tissue recovery to happen, including scar tissue maturation. The athlete is allowed to completely mobilize in full weight-bearing; however care needs to be taken using any flexion and rotation motions and no lifting will be allowed.

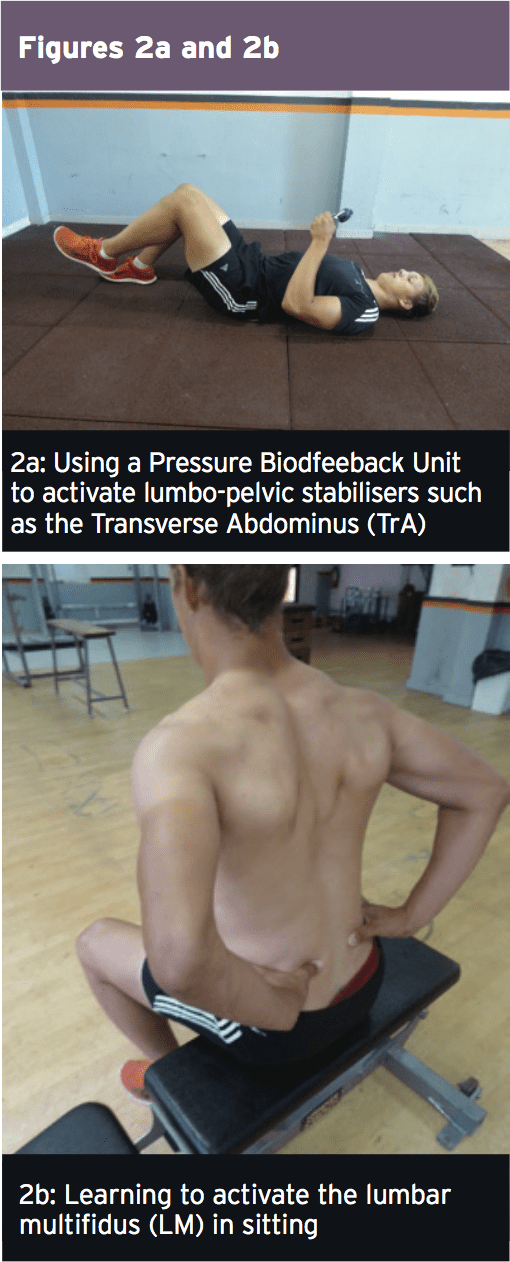

The athlete can begin with the physiotherapist with the objective to manage any gluteal and lumbar muscle trigger points and start nerve mobilization techniques that show how to engage the TrA and LM muscles (see Figures 2a and 2b). If the physiotherapist has access to your muscle stimulator (Compex), then this can be utilized in atrophy manner on the lumbar spine multifidus and erector spinae. The key criteria to exit this early phase are curable walking as well as also an Oswestry Disability Score of 41-60%.

Early Loading & Foundation

Early Loading & Foundation

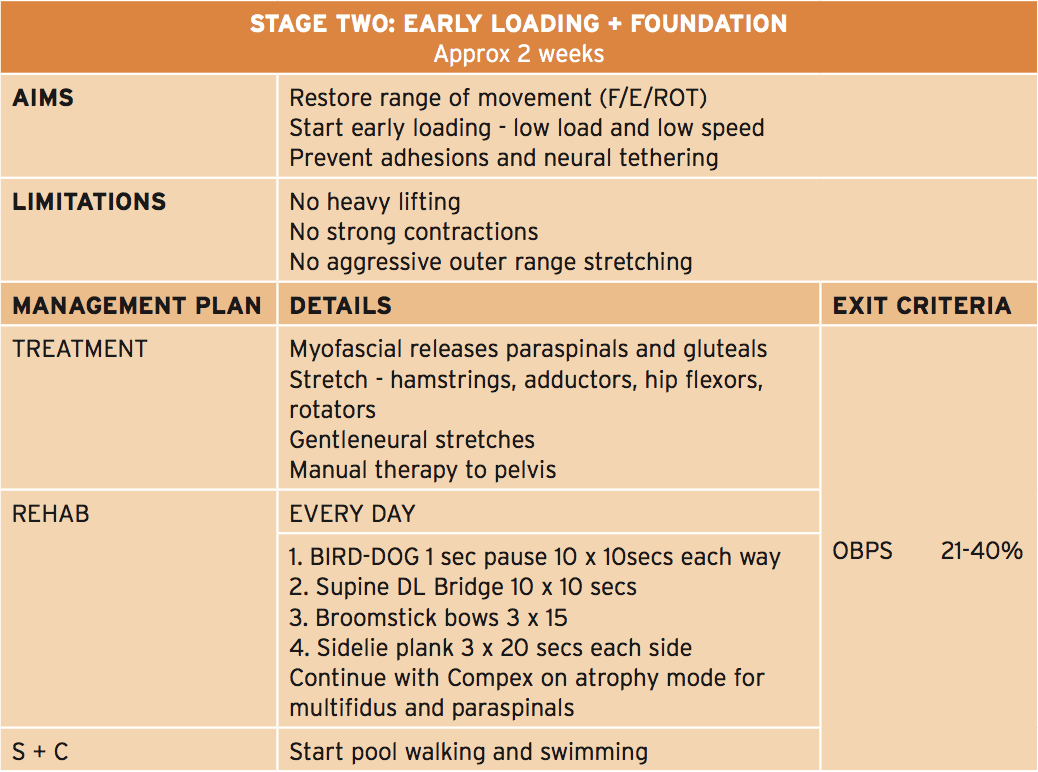

The primary feature of this phase is that the athlete can start early and low-load strength exercises focusing on muscle activation in a neutral spine position, along with a progressive selection of motion program to improve lumbar spine flexion, extension and rotation. In this stage that the physiotherapist will guide the athlete through safe and gentle stretches to your hip quadrant muscles like the hip flexors, gluteals, hamstrings and adductors. The athlete also lasts gentle neuro-mobilization exercises to advance the freedom of the sciatic nerve — an issue in this condition as neurological tethering is a chance as a result of scar tissue formation caused by the surgical procedure.

The primary feature of this phase is that the athlete can start early and low-load strength exercises focusing on muscle activation in a neutral spine position, along with a progressive selection of motion program to improve lumbar spine flexion, extension and rotation. In this stage that the physiotherapist will guide the athlete through safe and gentle stretches to your hip quadrant muscles like the hip flexors, gluteals, hamstrings and adductors. The athlete also lasts gentle neuro-mobilization exercises to advance the freedom of the sciatic nerve — an issue in this condition as neurological tethering is a chance as a result of scar tissue formation caused by the surgical procedure.

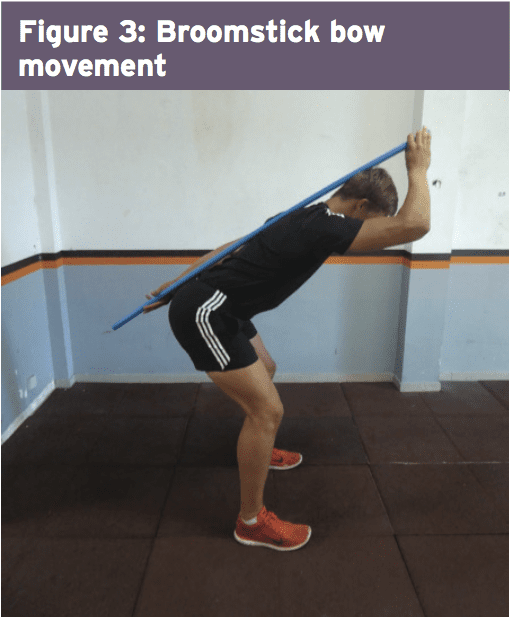

The athlete can also be encouraged to start hydrotherapy in the form of walking in water (waist high) along with swimming fitness center. In addition, he/she must start a string of low degree muscle activation drills in this stage (see Figure 3) that can be performed every day. This exercise teaches the athlete to hip flex (fashionable hinge) whilst maintaining a neutral spine. The neutral spine is maintained by using a light broomstick aligned with the back with the touch points being the occiput, the 6th thoracic vertebrae (T6) and the posterior sacrum.

Progressive Loading

Progressive Loading

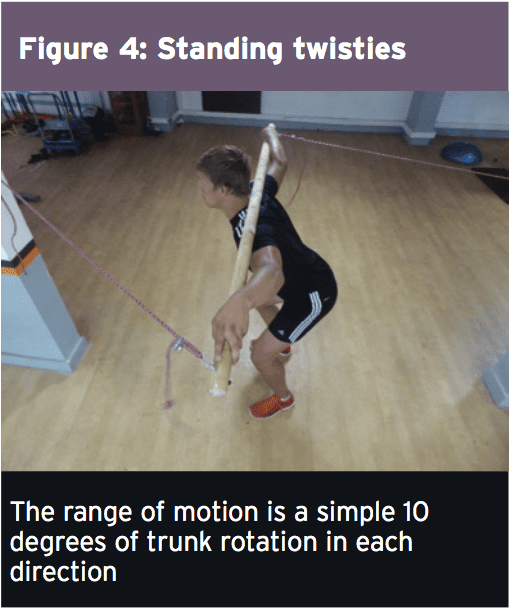

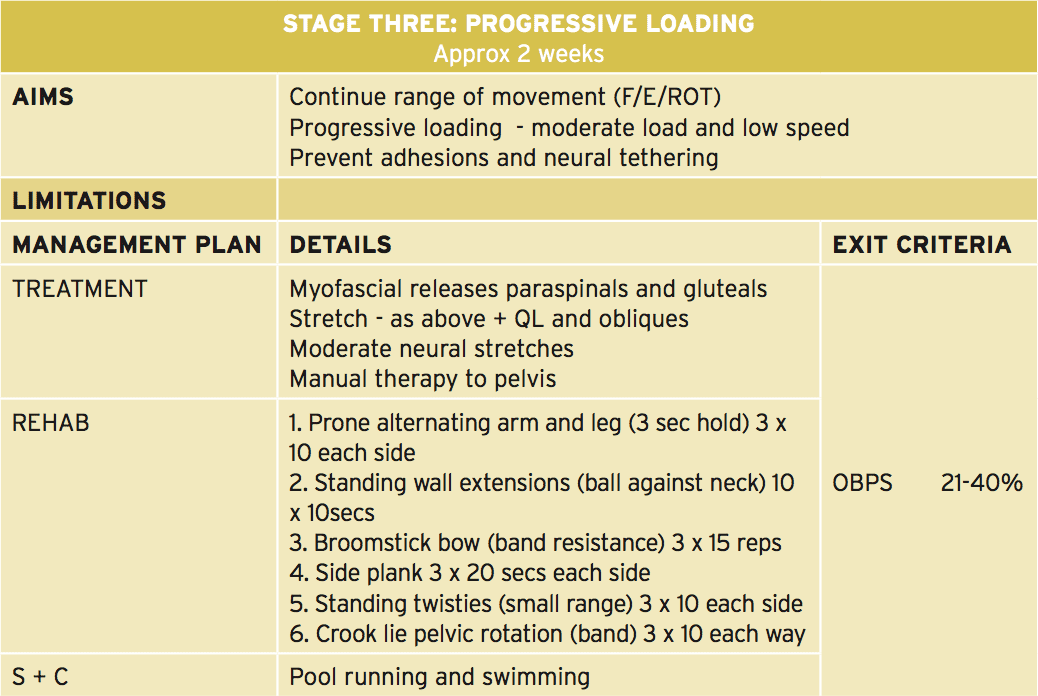

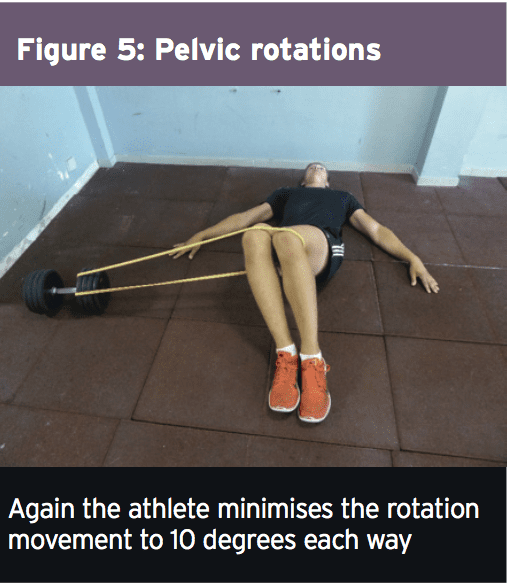

In this phase the athlete continues with a variety of movement progression along with the physiotherapist progresses manual therapy to the pelvis and lumbar spine. Neuro-mobilization techniques can also be progressed. The significant change in this phase is that the progression of load on many of the strength and muscle control exercises. Two exercises here are the ‘standing twisties’ and the ‘crook lying pelvic rotation’ exercise (Figures 4 and 5). These movements are the introductory spinning based movements. The primary progression about fitness drills is the athlete can begin pool running drills.

In this phase the athlete continues with a variety of movement progression along with the physiotherapist progresses manual therapy to the pelvis and lumbar spine. Neuro-mobilization techniques can also be progressed. The significant change in this phase is that the progression of load on many of the strength and muscle control exercises. Two exercises here are the ‘standing twisties’ and the ‘crook lying pelvic rotation’ exercise (Figures 4 and 5). These movements are the introductory spinning based movements. The primary progression about fitness drills is the athlete can begin pool running drills.

Load Accumulation

Load Accumulation

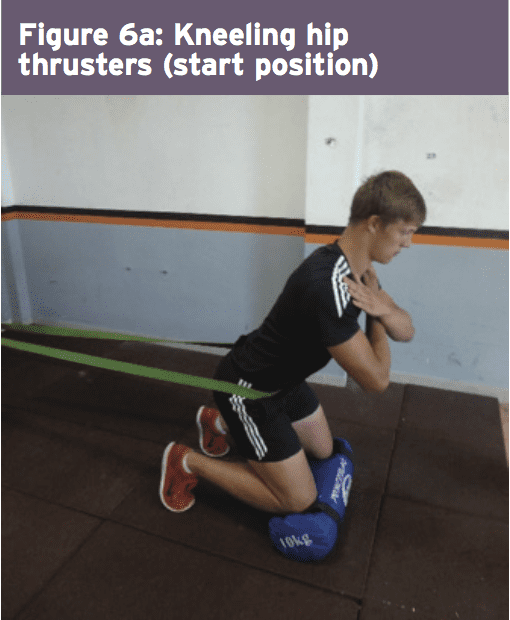

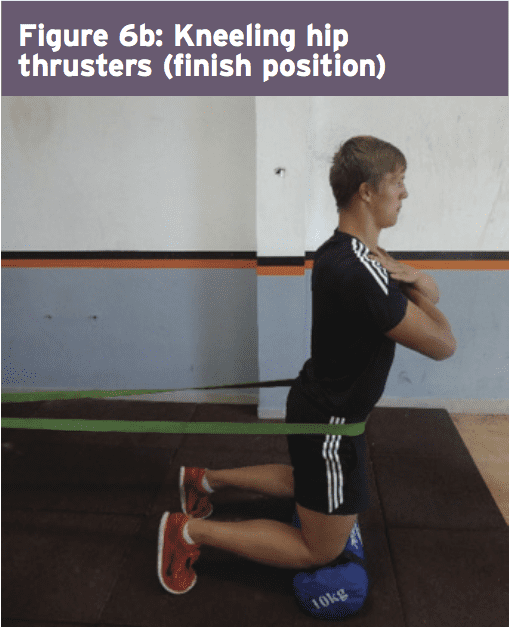

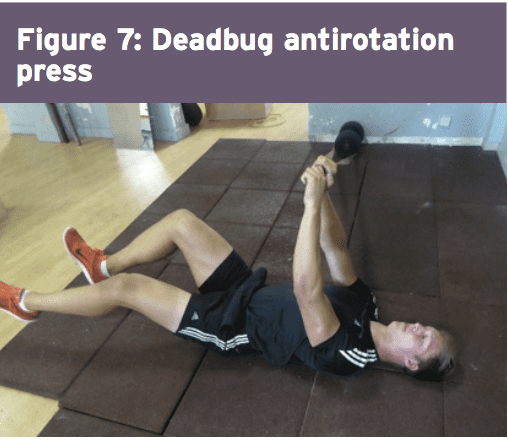

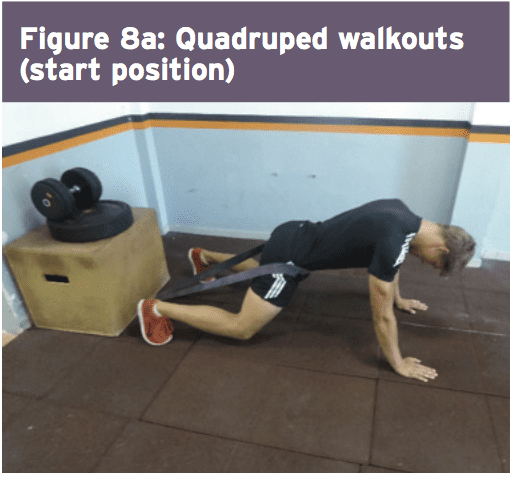

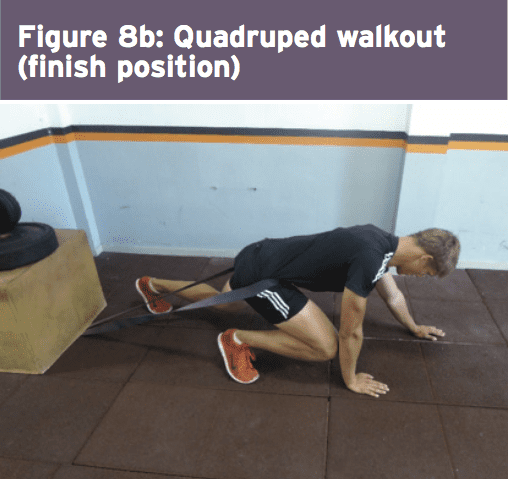

This is the stage where the athlete begins to advance the load in strength-based exercises. Resistance is used in the form of barbell load and band resistance. Three exceptional exercises performed here are the ‘kneeling hip thruster’, ‘deadbug antirotation press’ and also the ‘quadruped walkout’ (Figures 6-8 — explained in detail in the online database of exercises).

This is the stage where the athlete begins to advance the load in strength-based exercises. Resistance is used in the form of barbell load and band resistance. Three exceptional exercises performed here are the ‘kneeling hip thruster’, ‘deadbug antirotation press’ and also the ‘quadruped walkout’ (Figures 6-8 — explained in detail in the online database of exercises).

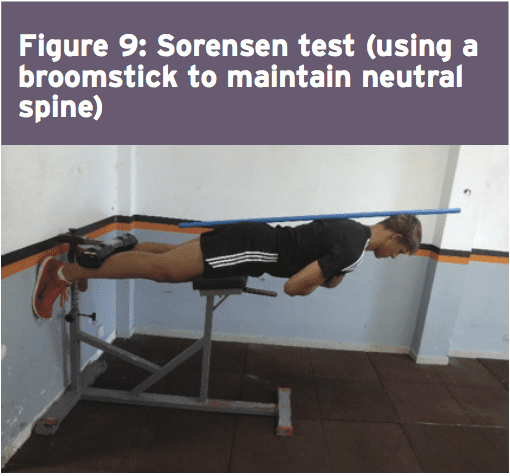

The athlete also begins running drills at this phase and it might be expected that as well as building running Amount, the athlete should progress over four weeks to close to full sprint speeds. This is also the stage whereby they would initiate mild to moderate sports special skills drills. Another characteristic of this stage is that the athlete starts the ‘Sorensen test’ exercise (Figure 9) and it will be expected that they can maintain the position for no less than 90 seconds before advancing to the next phase.

The athlete also begins running drills at this phase and it might be expected that as well as building running Amount, the athlete should progress over four weeks to close to full sprint speeds. This is also the stage whereby they would initiate mild to moderate sports special skills drills. Another characteristic of this stage is that the athlete starts the ‘Sorensen test’ exercise (Figure 9) and it will be expected that they can maintain the position for no less than 90 seconds before advancing to the next phase.

Maximum Load

In this final stage, the athlete spreads all core and strength exercises to maximum loads, and they work with the fitness trainer on coming to squat and functional fitness center lift movements. Skill progression can also be advanced alongside sprint and agility drills. The last exit standards prior to advancing to endless strength and training work is they have to keep the ‘Sorensen test’ for 180 seconds and their self documented Oswestry scale ought to be someplace between 0-20%.

References

1. Neurosurgical Focus. 2006;21:E4

2. Phys Sportsmed. 2005;33(4):21–7

3. Spine. 1996;21:1777-86

4. Neurosurgery 1992;30:861-7

5. Spine J. 2011;11(3):180–6

6. European Spine Journal. 2012. 21: 655-659

7. SPINE 1999;24:570-573

8. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(12):1247–51

9. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2604–8

10. Spine J. 2003;3:100–105

11. Spine. Apr 1 2010;35(7):825-8

12. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011:2 25–31

13. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1811-9

14. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:575-81

15. Physical Therapy. 2013. 93: 591- 596

16. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2010. 40(7). 402-412

17. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271-273

18. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:2803-2809

19. Phys Ther. 2001;81:776-788

20. Spine 1984, 9:106-119

21. Joint Bone Spine 73 (2006) 43–50

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: coach@elpasofunctionalmedicine.com

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card