Migraine pain is among one of the most common and debilitating conditions of the human population. As a result, many migraine cases are often misdiagnosed, leading to their improper treatment. With the proper treatment, however, a patient’s overall health and wellness as well as their quality of life may improve considerably. In addition, patient education is essential to help patients take appropriate self-care measures and for them to learn how to cope with the chronic nature of their condition. Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy and the use of medication has been previously compared to determine the effectiveness of each for migraine pain. The purpose of the following article is to demonstrate the efficacy of each migraine pain treatment.

Table of Contents

A Case Series of Migraine Changes Following a Manipulative Therapy Trial

Abstract

- Objective: To present the characteristics of four cases of migraine, who were included as participants in a prospective trial on chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for migraine.

- Method: Participants in a migraine research trial, were reviewed for the symptoms or clinical features and their response to manual therapy.

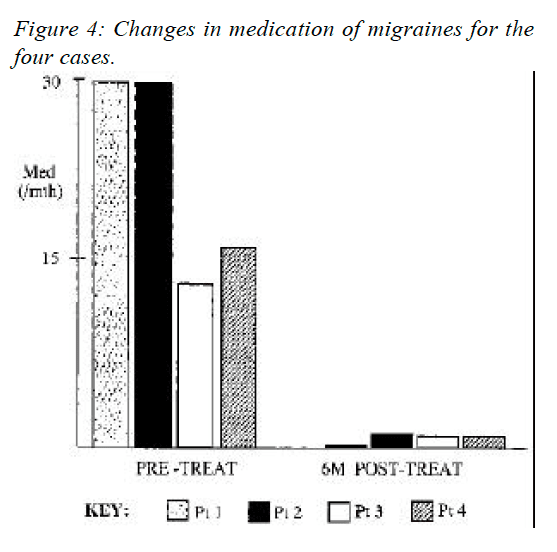

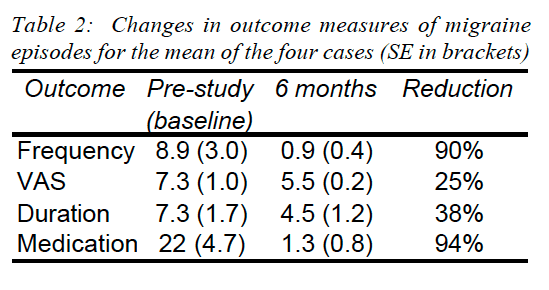

- Results: The four selected cases of migraine responded dramatically to SMT, with numerous self reported symptoms being either eliminated or substantially reduced. Average frequency of episodes was reduced on average by 90%, duration of each episode by 38%, and use of medication was reduced by 94%. In addition, several associated symptoms were substantially reduced, including nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia.

- Discussion: The various cases are presented to assist practitioners making a more informed prognosis.

- Key Indexing Terms (MeSH): Migraine, diagnosis, manual therapy.

Introduction

Migraine, in its various forms, affects approximately 12 to 15% of people throughout the world, with an estimated incidence in the USA of 6% of males and 18% of females (1). Depending on the severity of a migrainous attack it is apparent that most, if not all, of the body systems can be affected (2). Consequently migraine poses a substantial threat to regular sufferers, which debilitates them to varying degrees from slight to severe (3).

One early definition of migraine highlights some potential difficulties in research assessing treatment for migraine. “A familial disorder characterised by recurrent attacks of headache widely variable in intensity, frequency and duration. Attacks are commonly unilateral and are usually associated with anorexia, nausea and vomiting. In some cases they are preceded by, or associated with neurological and mood disturbances. All of the above characteristics are not necessarily present in each attack or in each patient” (4). (Migraine and headache of the World Federation of Neurology in 1969).

Some of the more common symptoms of migraine include headache, an aura, scotoma, photophobia, phonophobia, scintillations, nausea and/or vomiting (5).

The source of pain in migraines is to found in the intra- and extracranial blood vessels (6). The blood vessel walls are pain sensitive to distension, traction or displacement. The idiopathic dilation of cranial blood vessels, together with an increase in a pain-threshold-lowering substance, result in headache for migraine headache (7).

Migraine has been shown to be reduced following chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (8-18). In addition, other research suggests a potential role of musculoskeletal conditions in the aetiology of migraine (19-22). A misdiagnosis of migraine or cervicogenic headache could give a misleading positive result for improvement (23). Therefore, an accurate diagnosis needs to be made, based on standard accepted taxonomy.

A new classification system of headaches has been developed by the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS), which contains a main category covering migraine (24). However, this taxonomy system still has several areas of potential overlap or controversy regarding the diagnosis of the headache (23).

This paper presents three cases of migraine with aura (MA) and one of migraine without aura (MW), detailing their symptoms, clinical features and response to chiropractic Spinal Manulative Therapy (SMT). The authors hope to enhance practitioners knowledge for migraine conditions that may respond favourably with SMT.

Features of Migraine

The IHS defines migraines as having at least two of the following: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity, aggravated by routine physical activity. During the headache the person must also experience either nausea &/or vomiting, and photophobia &/or phonophobia (24). In addition, there is no suggestion either by history, physical or neurological examination that the person has a headache listed in groups 5-11 of their classification system (23-25).

A previous study by the author has detailed features of the different classifications of migraine (8). The aura is the distinguishing feature between the old classifications of common (MW) and classic migraine (MA) (24). It has been described by migraine sufferers as an opaque object, or a zigzag line around a cloud, even cases of tactile hallucinations have been recorded (6,7). The most common auras consist of homonymous visual disturbances, unilateral parathesias &/or numbness, unilateral weakness, aphasia or unclassifiable speech difficulty.

The potential mechanisms for the different migraine types are poorly understood. There have been a number of aetiologies proposed in the literature, but none seem to be able to explain all the potential symptoms experienced by migraine sufferers (26). The IHS describe changes in blood composition and platelet function as a triggering role. Processes which occur in the brain act via the trigemino-vascular system and the intra and extracranial vasculature and perivascular spaces (24).

Methodology

Based on a previous reported study (9) which involved 32 subjects who received chiropractic SMT for MA, three cases are presented which were selected due to the significant changes the patient experienced.

People with migraines were advertised for participation in the study, via the radio and newspapers within a local region of Sydney. All applicants completed a questionnaire, developed from Vernon (27) and has been reported in a previous study (9).

The participants to take part in the trial were selected according to responses in the questionnaire of specific symptoms. The criteria for MA diagnosis was compliance with at least 5 out of the following indicators: reaction to pain requiring cessation of activities or the need to seek a quiet dark area; pain located around the temples; pain described as throbbing; associated symptoms of nausea, vomiting, aura, photophobia or phonophobia; migraine precipitated by weather changes; migraine aggravated by head or neck movements; previous diagnosis of migraine by a specialist; and a family history of migraine.

Participants also had to experience migraine at least once a month, but not daily and the migraines could not have been initiated by trauma. Participants were excluded from the study if there were contra-indications to SMT, such as meningitis or cerebral aneurysm. In addition, participants with temporal arteritis, benign intracranial hypertension or space occupying lesions, were also excluded due to safety aspects.

The trial was conducted over six months, and consisted of 3 stages: two months pre-treatment, two months treatment, and two months post treatment. Participants completed diaries during the entire trial noting the frequency, intensity, duration, disability, associated symptoms and use of medication for each migraine episode. In addition, clinic records were compared to their diary entries of migraine episodes. Concurrently, the subjects were contacted by telephone by the author every two weeks and asked to describe the migraine episodes for comparison to their diaries.

A detailed history of the patients’ subjective pain features was taken during the initial consultation. This included the type of pain, duration, onset, severity, radiation, aggravating and relieving factors. The history also included medical features, a systems review for potential pathologies, previous treatments and its effects. Assessment of subluxation included: orthopaedic and neurological testing, segmental springing, mobility measures such as visual estimation of range of motion, assessment of previous radiographs, specific chiropractic vertebral testing procedures, as well as response of the patient to SMT.

In addition, several vascular investigations were performed where indicated, which include: vertebral artery test, manipulative provocation test, blood pressure assessment, and abdominal aortic aneurysm screening.

During the treatment period, the subjects continued to record migraine episodes in their diary, and receive telephone calls from the authors. Treatment consisted of short amplitude, high velocity spinal manipulative thrusts, or areas of fixation determined by the physical examination. Comparison was made of initial baseline episodes of migraine prior to commencement of the study and at six months following its cessation.

Case 1

A 25 year old, 65kg Caucasian male presented with neck pain which had commenced in early childhood, that he felt may have been related to his prolonged birth. During the history the patient stated that he suffered a regular migraine headaches (3-4 per week) which he supposed was related to a motor vehicle accident, two years prior to his presentation. He reported that his “migraine” symptoms were a unilateral throbbing headache, an aura, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and photophobia. Sleep tended to alleviate the symptoms and he required Allegren medication (25mg) on a daily basis.

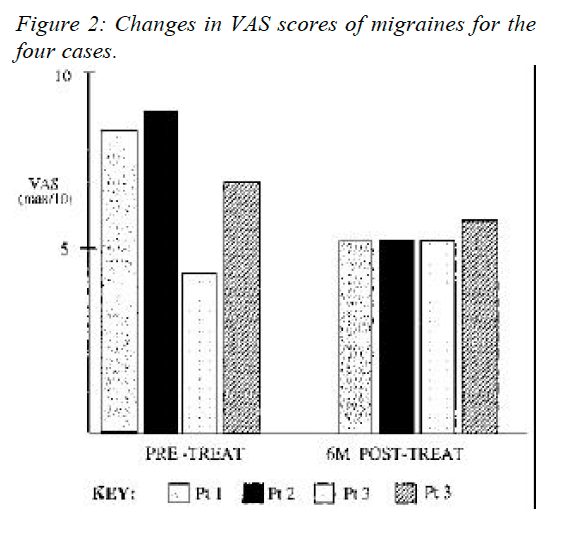

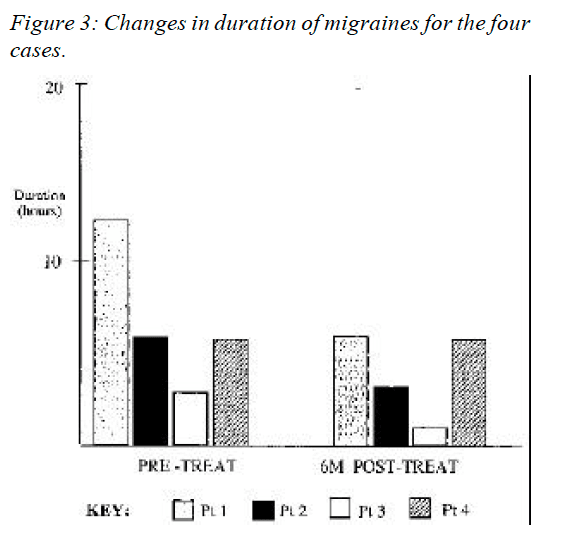

From diaries the patient was required to complete in the study, a migraine would occur 14 times a month, last an average 12.5 hours and he could perform duties after 8 hours. In addition a visual analogue scale score (VAS) for an average episode was 8.5 out of a possible maximum score of ten, corresponding to a description of “terrible” pain.

On examination, he was found to have sensitive suboccipital and upper cervical musculature, and decreased range of motion at the joint between the occiput and first cervical vertebra, the atlanto-occipital facet joint (Occ-C1), coupled with pain on flexion and extension of the cervical spine. He also had significant reduction in thoracic spine motion and an increase in thoracic kyphosis.

Treatment

The patient received chiropractic adjustments (described above) to his Occ-C1 joint, upper thoracic spine and the affected hypertonic musculature. An initial course of 16 diversified chiropractic treatments was conducted as part of a research program that the patient was participating in. The program involved recording several features for every migraine episode, including visual analogue scores, duration, medication and time before they could return to normal activities. In addition, he was shown some stretches and other exercises for his neck muscles and proved compliant.

Outcome

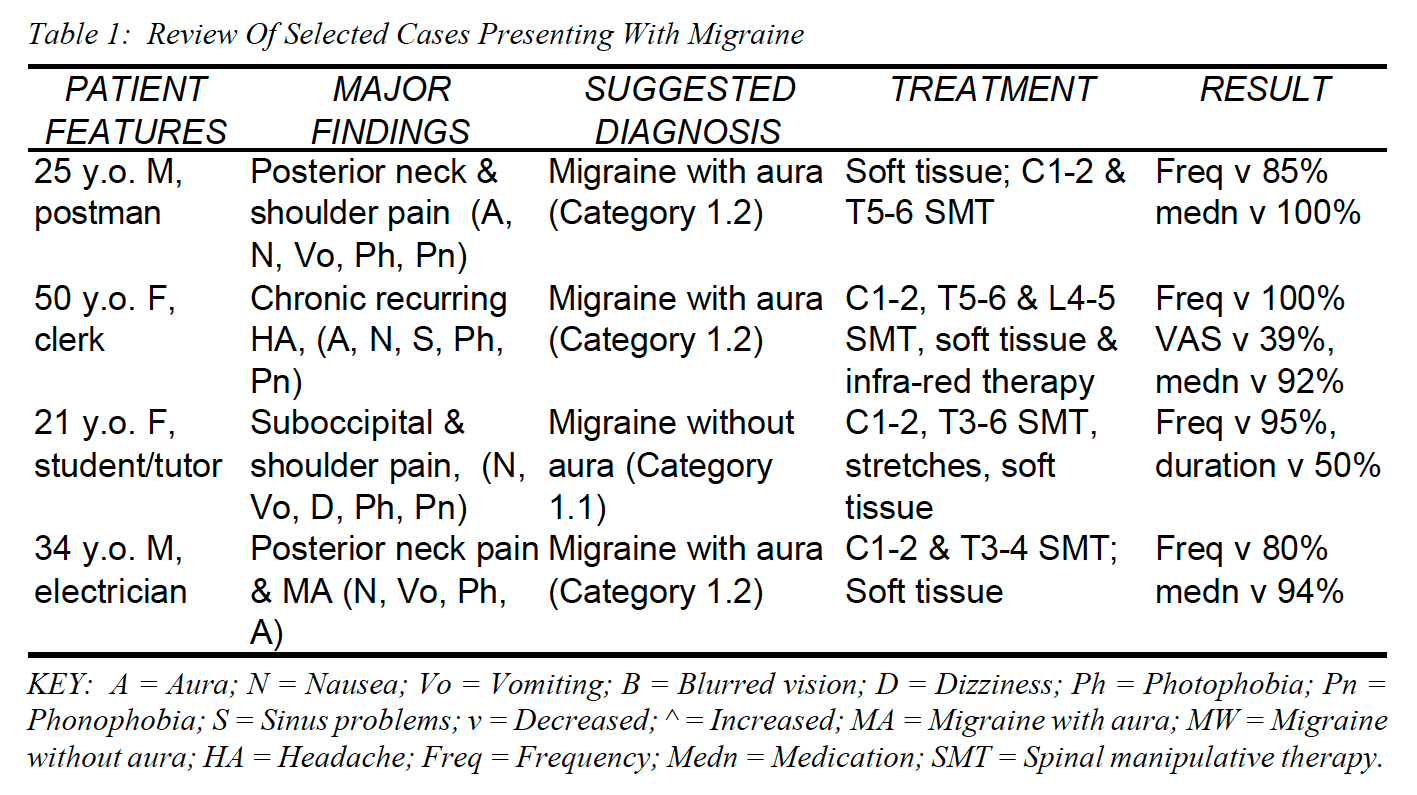

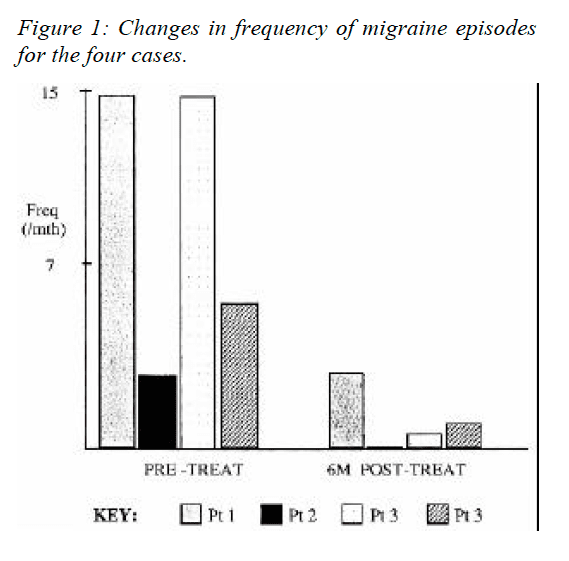

The patient reported a dramatic improvement after the course of treatment and had noticeably reduced frequency and intensity of migraines. This had continued when the patient was contacted at a period of 6 months after the study had ceased (Fig 1). At that point the patient reported having 2 migraines a month, with a VAS score of 5 out of ten, and the average duration had fallen to 7 hours (Fig’s 1-3). In addition, he now used no medication and noted that he no longer experienced nausea, vomiting, photophobia or phonophobia (Table 1).

Case 2

A 43 year old female university clerk presented complaining of chronic recurring headaches each lasting on average five days, sinus trouble due to allergy, and disturbed vision. The patient stated she experienced “migraines” which had been occurring since the age of eight. During the migraines she experienced nausea, visual disturbances, photophobia, phonophobia and scotoma. The pain usually began around her right eye but would often change to the left temple. She did not describe the pain as throbbing and the pain only stopped activities on a few occasions each year.

The patient stated she experienced the migraines once a month, except during springtime, when the migraines would occur at least once a week. She had been prescribed hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for twelve months following menopause, which had not changed the migraines. She also reported a VAS score of eight for an average episode and that an average episode lasted between six to eight hours.

In her history she reported that she had experienced many falls while horse riding between the ages of eight to ten. However, she believed that no bones were broken at the time of the falls, although this was not confirmed by radiographs at the time of injury. She had two children and was active, currently playing tennis, walking and was a keen gardener. Her past treatment included non- prescription medication for her sinus problems (Teldane), however this did not seem to relieve the migraine. The patient stated she had previously had pethadine injections due to the severity of the migraines.

On examination she had an increased thoracic kyphosis, associated Trapezius hypertonicity and trigger points. She exhibited slight scoliosis (negative on Adams test) in the lumbar and thoracic regions. The patient also had moderate limitation in cervical spine mobility, notably in left lateral flexion and right rotation.

Treatment

Treatment consisted of diversified chiropractic spinal adjustments, especially to the C1-2, T5-6, L4-5 joints to correct the restriction of movement. Vibrator massage, and infra-red therapy were used to complement the treatment, releasing muscles spasm of the region before the adjustments were delivered. The patient was given 14 treatments over the two months of the research trial. Following the initial treatment she experienced some moderate neck pain which resolved following the next session.

Outcome

When contacted six months following the study, the patient stated the migraines had not experienced a migraine in the last four months. The last episode she had noted a VAS score reduced to four, the average duration had reduced to three days and she had now reduced her medication to nil (Fig’s 1-4). In addition, she now experienced minor nausea, no photophobia or phonophobia, and she had substantially improved neck mobility. She had continued to have chiropractic treatment at a frequency of once a month, following the end of the research trial.

Case 3

A 21 year old female, 171cm tall Caucasian presented with a chief complaint of severe migraines. Each episode lasted two to four hours, at a frequency of three to four episodes per week, and they had occurred for five years. The patient reported moderate posterior neck and shoulder pain, associated with the migraines. She also believed the initial migraine to be induced by stress and subsequent episodes were also aggravated by emotional stress. The patient reported no other health problems except very mild hypotension, for which she was not taking medication.

The patient’s migraines were located in the frontal, temporal and occipital regions bilaterally. No symptoms occurred premonitory to the onset of her migraines, nor did she experience visual disturbances prior to or during the migraine episodes. She described the pain as a constant dull ache, which was local and she did not complain of any parathesias.

At the initial visit, she rated each migraine between 4 and 5 on a VAS of 1-10. She also noted she experienced nausea, vomiting, dizziness, photophobia and phonophobia.

The cervical ranges of motion were restricted, predominantly in right rotation. Palpation findings were obvious at trapezius, suboccipital and supra scapulae muscles due to increased tone, colour and temperature. Motion palpation indicated restricted movement of the C1-2 facet joint on the right side. Further palpation of the supra scapular and suboccipital indicated myofibrotic tissue. Neurological tests such as Rhombergs, and vertebrobasilar (Maines) test, were negative.

Treatment

The initial treatment was muscle stripping technique aided by a masseter machine massage across the muscle fibres of the trapezius, suprascapularis and temporal regions. The patient also had a cervical adjustment of C1- 2, and adjustment to the T3-4 & T4-5 segments.

The patient was seen three days later, at which point she reported that her neck was less painful. However, she still complained of right neck pain and dizziness. Examination revealed passive motion restriction at C1-2 motion segment. Her thoracic spine was found to be restricted at segment T5-6. In addition, she had mild to moderate hypertonicity in suboccipital and cervical paraspinal muscles and supra scapular area. She was again treated with adjustments and soft tissue technique. The C1-2 restriction to the right was adjusted with a cervical adjustment. The T5-6 restriction was also adjusted and the myofibrotic tissues were treated with the masseter.

The patient returned four days later. She reported that her migraine had improved. She no longer experienced the symptoms of a non-classical migraine. However, the pressure sensation was still present around her head, but less so than prior to the commencement of treatment. No neck pain was reported. Examination revealed a passive motion restriction of C1-2 motion segment. There was hypertonicity in the suboccipital and supra scapular muscles. The patient was treated with a cervical adjustment at C1-2 and muscle work on the above muscle groups. Neck stretching exercises were also advised.

The patient was seen a total of thirteen times over a two month period, and stated that her migraine episodes had reduced significantly at the last treatment. In addition, she was no longer experiencing neck pain. Examination revealed passive motion restriction at the C1-2 motion segment, which was reduced by adjustment.

Outcome

The patient was contacted six months after the trial for a follow-up, at which point she reported she had experienced a reduction of migraine episodes to once every two months. However, her VAS scores for an average episode was now 5.5, but the duration of an average episode was reduced by 50%. In addition, she noted a reduction in photophobia and phonophobia, but still experienced some dizziness. The patient also noted a reduction in use of medication from three Nurofen a week (12 per month) to three per month, representing a 75% reduction (Fig’s 1- 4).

Case 4

A 34 year old, 75kg Caucasian male presented with neck pain and migraines which had commenced after he had hit his head whilst surfing at a beach. This incident occurred when the patient was 19 years old but the patient said the migraines had peaked at 25 years of age. The patient stated that at 25 years of age he suffered a migraine headaches (three to four times per week) but now in the last year prior to his presentation he experienced them twice a week. He reported that his migraines started in the suboccipital region, and radiated to his right eye. He also reported they were a unilateral throbbing headache, an aura, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and photophobia. The patient stated taking aspirin and mersyndol medication approximately four to five times a week.

The patient reported that an average episode lasted twelve to eighteen hours and he could perform duties after eight to ten hours. In addition a visual analogue scale score (VAS) for an average episode was 7.0 out of a possible maximum score of ten, corresponding to a description of “moderate” pain. He also reported that he had osteopathic treatment approximately three years earlier, which had given some short term relief, however, physiotherapy had proven ineffective.

On examination, he was found to have significant reduction in thoracic spine motion and an increase in thoracic kyphosis, and decreased range of motion at the joint between the first and second cervical vertebra (C1- 2), the atlanto-occipital facet joint (Occ-C1), coupled with pain on flexion and extension of the cervical spine. He also had sensitive suboccipital and upper cervical musculature, especially the upper Trapezius muscle.

Treatment

The patient received chiropractic diversified adjustments to his C1-2 joint, upper thoracic spine and the affected hypertonic musculature. After a course of 14 treatments (conducted as part of a research program) the patient found he was experiencing one migraine per fortnight. The patient also reported that the nausea had decreased and that the aura was less significant.

The patient reported the improvement after the initial treatment had continued when the patient was contacted 6 months after the study had ceased. At that point the patient reported having one migraine a month, and that the VAS score had fallen to 6 out of ten. However, the average duration and return to normal activities time had remain the same as before the treatment had commenced. The patient reported that he now used only one medication per month and that he no longer experienced nausea, vomiting, and the aura (Fig’s 1-4).

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insight

“How does the effectiveness of chiropractic care and the use of medication vary when it comes to migraine pain?” Chiropractic migraine pain treatment, such as chiropractic spinal manipulative treatment or spinal manipulation, is commonly utilized to help improve as well as manage migraine symptoms. Many healthcare professionals also frequently use medication, such as amitriptyline, to help relieve migraine symptoms although this treatment option may only temporarily relieve the symptoms rather than treat the condition from the source. Chiropractic care and the use of medication can be used together to help increase the relief of the treatments, as recommended by a healthcare professional. Several evidence-based studies, like the ones in the article, have demonstrated the effectiveness of chiropractic migraine pain treatment, however, more research studies are required to determine their specific result on migraine pain management. Furthermore, other research studies have shown that medication may be as effective as chiropractic spinal manipulative treatment but was associated with more side effects. Common side effects of medications like amitriptyline include: drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, trouble urinating or weight gain. Additional assessments on the effectiveness of spinal manipulation and amitriptyline is needed.

Conclusion

These four case studies highlight an apparent significant reduction in disability associated with migraines (Table 1). The conclusions are limited however, because the study does not contain a control group for comparison of placebo effect. Therefore chiropractic SMT appears to have significantly reduced migraine disability for these individuals.

Practitioners need to be critically aware of diagnostic criteria when presenting studies or case studies on effectiveness of their treatment (8). This is especially important in presentation of migraine and manipulative therapy research (12, 23).

Changes in outcome measures of migraine episodes for the mean of the four cases revealed some interesting findings (Table 2 ). As can be seen in the table, the frequency of episodes and the use of medication were substantially reduced for the four cases. However, one cannot conclude that this could be the case for other migraine sufferers due to the small number of cases presented.

Acknowledgement

The author greatly appreciates the contribution of Dr Dave Mealing in the preparation of the paper.

A Randomized Controlled Trial of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Migraine.

Abstract

- Objective: To assess the efficacy of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) in the treatment of migraine.

- Design: A randomized controlled trial of 6 months’ duration. The trial consisted of 3 stages: 2 months of data collection (before treatment), 2 months of treatment, and a further 2 months of data collection (after treatment). Comparison of outcomes to the initial baseline factors was made at the end of the 6 months for both an SMT group and a control group.

- Setting: Chiropractic Research Center of Macquarie University.

- Participants: One hundred twenty-seven volunteers between the ages of 10 and 70 years were recruited through media advertising. The diagnosis of migraine was made on the basis of the International Headache Society standard, with a minimum of at least one migraine per month.

- Interventions: Two months of chiropractic SMT (diversified technique) at vertebral fixations determined by the practitioner (maximum of 16 treatments).

- Main Outcome Measures: Participants completed standard headache diaries during the entire trial noting the frequency, intensity (visual analogue score), duration, disability, associated symptoms, and use of medication for each migraine episode.

- Results: The average response of the treatment group (n = 83) showed statistically significant improvement in migraine frequency (P < .005), duration (P < .01), disability (P < .05), and medication use (P< .001) when compared with the control group (n = 40). Four persons failed to complete the trial because of a variety of causes, including change in residence, a motor vehicle accident, and increased migraine frequency. Expressed in other terms, 22% of participants reported more than a 90% reduction of migraines as a consequence of the 2 months of SMT. Approximately 50% more participants reported significant improvement in the morbidity of each episode.

- Conclusion: The results of this study support previous results showing that some people report significant improvement in migraines after chiropractic SMT. A high percentage (>80%) of participants reported stress as a major factor for their migraines. It appears probable that chiropractic care has an effect on the physical conditions related to stress and that in these people the effects of the migraine are reduced.

Spinal Manipulation vs. Amitriptyline for the Treatment of Chronic Tension-Type Headaches: a Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

- Objective: To compare the effectiveness of spinal manipulation and pharmaceutical treatment (amitriptyline) for chronic tension-type headache.

- Design: Randomized controlled trial using two parallel groups. The study consisted of a 2-wk baseline period, a 6-wk treatment period and a 4-wk posttreatment, follow-up period.

- Setting: Chiropractic college outpatient clinic.

- Patients: One hundred and fifty patients between the ages of 18 and 70 with a diagnosis of tension-type headaches of at least 3 months’ duration at a frequency of at least once per wk.

- Interventions: 6 wk of spinal manipulative therapy provided by chiropractors or 6 wk of amitriptyline treatment managed by a medical physician.

- Main Outcome Measures: Change in patient-reported daily headache intensity, weekly headache frequency, over-the-counter medication usage and functional health status (SF-36).

- Results: A total of 448 people responded to the recruitment advertisements; 298 were excluded during the screening process. Of the 150 patients who were enrolled in the study, 24 (16%) dropped out: 5 (6.6%) from the spinal manipulative therapy and 19 (27.1%) from the amitriptyline therapy group. During the treatment period, both groups improved at very similar rates in all primary outcomes. In relation to baseline values at 4 wk after cessation of treatment, the spinal manipulation group showed a reduction of 32% in headache intensity, 42% in headache frequency, 30% in over-the-counter medication usage and an improvement of 16% in functional health status. By comparison, the amitriptyline therapy group showed no improvement or a slight worsening from baseline values in the same four major outcome measures. Controlling for baseline differences, all group differences at 4 wk after cessation of therapy were considered to be clinically important and were statistically significant. Of the patients who finished the study, 46 (82.1%) in the amitriptyline therapy group reported side effects that included drowsiness, dry mouth and weight gain. Three patients (4.3%) in the spinal manipulation group reported neck soreness and stiffness.

- Conclusions: The results of this study show that spinal manipulative therapy is an effective treatment for tension headaches. Amitriptyline therapy was slightly more effective in reducing pain at the end of the treatment period but was associated with more side effects. Four weeks after the cessation of treatment, however, the patients who received spinal manipulative therapy experienced a sustained therapeutic benefit in all major outcomes in contrast to the patients that received amitriptyline therapy, who reverted to baseline values. The sustained therapeutic benefit associated with spinal manipulation seemed to result in a decreased need for over-the-counter medication. There is a need to assess the effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy beyond four weeks and to compare spinal manipulative therapy to an appropriate placebo such as sham manipulation in future clinical trials.

In conclusion, the following research studies demonstrated the effectiveness of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy while one research study compared it with the use of amitriptyline for migraine. The article concludes that both chiropractic migraine pain treatment as well as medication were significantly effective in the improvement of migraine headache, however, amitriptyline is reported to present various side effects. Finally, patients may choose the best possible treatment for their migraine pain, as recommended by a healthcare professional. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

1. Lipton RB, Stewart WF. Migraine in the United States: a review of epidemiology and health care use. Neurology 1993; 43(Suppl 3): S6-10.

2. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentous DD, et al. Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. JAMA 1992; 267: 64-9.

3. King J. Migraine in the Workplace. Brainwaves. Australian Brain Foundation 1995. Hawthorn, Victoria.

4. Wolff’s Headache and other head pain. Revised by Dalessio DJ. 3rd Ed 1972 Oxford University Press, New York.

5. Linet OS, Stewart WF, Celentous DD, et al. An epidemiological study of headaches among adolescents and young adults. JAMA 1989; 261: 221-6.

6. Anthony M. Migraine and its Management, Australian Family Physician 1986; 15(5): 643-9.

7. Sjasstad O, Fredricksen TA, Sand T. The localisation of the initial pain of attack: a comparison between classic migraine and cervicogenic headache. Functional Neurology 1989; 4: 73-8

8. Tuchin PJ, Bonello R. Classic migraine or not classic migraine, that is the question. Aust Chiro & Osteo 1996; 5: 66-74.

9. Tuchin PJ. The Efficacy Of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) In The Treatment Of Migraine – A Pilot Study. Aust Chiro & Osteo 1997; 6: 41-7.

10. Parker GB, Tupling H, Pryor DS. A Controlled Trial of Cervical Manipulation for Migraine, Aust NZ J Med 1978; 8: 585-93.

11. Hasselburg PD. Commission of Inquiry Into Chiropractic. Chiropractic in New Zealand. 1979 Government Printing Office New Zealand.

12. Parker GB, Tupling H, Pryor DS. Why Does Migraine Improve During a Clinical Trial? Further Results from a Trial of Cervical Manipulation for Migraine. Aust NZ J Med 1980; 10: 192-8.

13. Vernon H, Dhami MSI. Vertebrogenic Migraine, J Canadian Chiropractic Assoc 1985; 29(1): 20-4.

14. Wight JS. Migraine: A Statistical Analysis of Chiropractic Treatment. J Am Chiro Assoc 1978; 12: 363-7.

15. Vernon H, Steiman I, Hagino C. Cervicogenic Dysfunction in muscle contraction headache and migraine: a descriptive study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992; 15: 418-29.

16. Whittingham W, Ellis WS, Molyneux TP. The effect of manipulation (Toggle recoil technique) for headaches with upper cervical joint dysfunction: a case study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994; 17(6): 369-75.

17. Lenhart LJ. Chiropractic Management of Migraine without Aura: A case study. JNMS 1995; 3: 20-6.

18. Tuchin PJ, Scwafer T, Brookes M. A Case Study of Chronic Headaches. Aust Chiro Osteo 1996; 5: 47- 53.

19. Nelson CF. The tension headache, migraine continuum: A hypothesis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1994; 17(3): 157-67.

20. Kidd R, Nelson C. Musculoskeletal dysfunction of the neck in migraine and tension headache. Headache 1993; 33: 566-9.

21. Milne E. The Mechanism and treatment of migraine and other disorders of cervical and postural dysfunction. Cephalgia 1989; 9(Suppl 10): 381-2.

22. Young K, Dharmi M. The Efficacy Of cervical manipulation as opposed to pharmacological therapeutics in the treatment of migraine patients. Transactions of the Consortium for Chiropractic Research. 1987.

23. Marcus DA. Migraine and tension type headaches: the questionable validity of current classification systems. Pain 1992; 8: 28-36.

24. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache, Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalgia 1988; 9(Suppl 7): 1-93.

25. Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olsen J. Interactions between migraine and tension type headaches in the general population. Arch Neurol 1992; 49: 914-8.

26. Vernon H. Upper Cervical Syndrome: Cervical Diagnosis and Treatment. In Vernon H. (Ed): Differential Diagnosis of Headache. 1988 Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins.

27. Vernon HT. Spinal manipulation and headache of cervical origin. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1989; 12: 455-68.

Additional Topics: Neck Pain

Neck pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. According to statistics, automobile accident injuries and whiplash injuries are some of the most prevalent causes for neck pain among the general population. During an auto accident, the sudden impact from the incident can cause the head and neck to jolt abruptly back-and-forth in any direction, damaging the complex structures surrounding the cervical spine. Trauma to the tendons and ligaments, as well as that of other tissues in the neck, can cause neck pain and radiating symptoms throughout the human body.

IMPORTANT TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: A Healthier You!

OTHER IMPORTANT TOPICS: EXTRA: Sports Injuries? | Vincent Garcia | Patient | El Paso, TX Chiropractor

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: coach@elpasofunctionalmedicine.com

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card