While computed tomography scanning, or CT scans, of the cervical spine are frequently utilized to help diagnose neck injuries, simple radiographs are still commonly performed for patients who have experienced minor cervical spine injuries with moderate neck pain, such as those who have suffered a slip-and-fall accident. Imaging diagnostic assessments may reveal underlying injuries and/or aggravated conditions to be more severe than the nature of the trauma. The purpose of the article is to demonstrate the significance of cervical spine radiographs in the trauma patient.

Table of Contents

Abstract

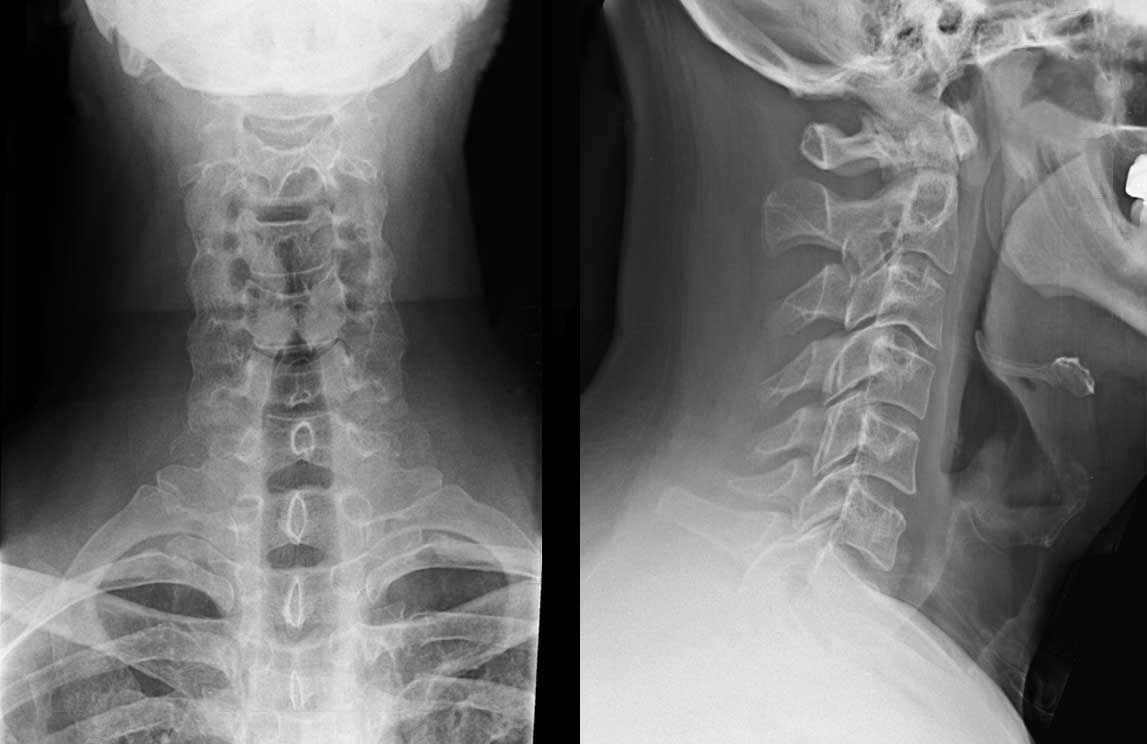

Significant cervical spine injury is very unlikely in a case of trauma if the patient has normal mental status (including no drug or alcohol use) and no neck pain, no tenderness on neck palpation, no neurologic signs or symptoms referable to the neck (such as numbness or weakness in the extremities), no other distracting injury and no history of loss of consciousness. Views required to radiographically exclude a cervical spine fracture include a posteroanterior view, a lateral view and an odontoid view. The lateral view must include all seven cervical vertebrae as well as the C7-T1 interspace, allowing visualization of the alignment of C7 and T1. The most common reason for a missed cervical spine injury is a cervical spine radiographic series that is technically inadequate. The “SCIWORA” syndrome (spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality) is common in children. Once an injury to the spinal cord is diagnosed, methylprednisolone should be administered as soon as possible in an attempt to limit neurologic injury.

Radiographs continue to be used as a first-line imaging diagnostic assessment modality in the evaluation of patients with suspected cervical spine injuries. The aim of cervical spine radiographs is to confirm the presence of a health issue in the complex structures of the neck and define its extent, particularly with respect to instability. Multiple views may generally be necessary to provide optimal visualization.

Dr. Alex Jimenez D.C., C.C.S.T.

Introduction

Although cervical spine radiographs are almost routine in many emergency departments, not all trauma patients with a significant injury must have radiographs, even if they arrive at the emergency department on a backboard and wearing a cervical collar. This article reviews the proper use of cervical spine radiographs in the trauma patient.

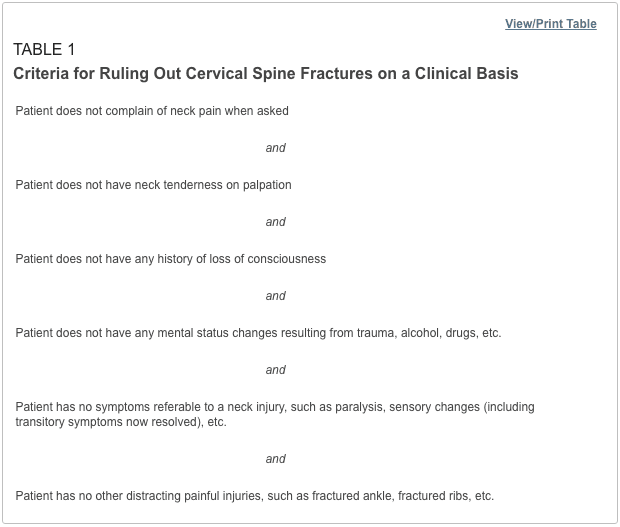

Low-risk criteria have been defined that can be used to exclude cervical spine fractures, based on the patient’s history and physical examination.1–6 Patients who meet these criteria (Table 1) do not require radiographs to rule out cervical fractures. However, the criteria apply only to adults and to patients without mental status changes, including drug or alcohol intoxication. Although studies suggest that these criteria may also be used in the management of verbal children,7–9 caution is in order, since the study series are small, and the ability of children to complain about pain or sensory changes is variable. An 18-year-old patient can give a more reliable history than a five-year-old child.

Some concern has been expressed about case reports suggesting that “occult” cervical spine fractures will be missed if asymptomatic trauma patients do not undergo radiography of the cervical spine.10 On review, however, most of the reported cases did not meet the low-risk criteria in Table 1. Attention to these criteria can substantially reduce the use of cervical spine radiographs.

Cervical Spine Series and Computed Tomography

Once the decision is made to proceed with a radiographic evaluation, the proper views must be obtained. The single portable cross-table lateral radiograph, which is sometimes obtained in the trauma room, should be abandoned. This view is insufficient to exclude a cervical spine fracture and frequently must be repeated in the radiographic department.11,12 The patient’s neck should remain immobilized until a full cervical spine series can be obtained in the radiographic department. Initial films may be taken through the cervical collar, which is generally radiolucent. An adequate cervical spine series includes three views: a true lateral view, which must include all seven cervical vertebrae as well as the C7-T1 junction, an anteroposterior view and an open-mouth odontoid view.13

If no arm injury is present, traction on the arms may facilitate visualization of all seven cervical vertebrae on the lateral film. If all seven vertebrae and the C7-T1 junction are not visible, a swimmer’s view, taken with one arm extended over the head, may allow adequate visualization of the cervical spine. Any film series that does not include these three views and that does not visualize all seven cervical vertebrae and the junction of C7-T1 is inadequate. The patient should be maintained in cervical immobilization, and plain films should be repeated or computed tomographic (CT) scans obtained until all vertebrae are clearly visible. The importance of obtaining all of these views and visualizing all of the vertebrae cannot be overemphasized. While some missed cervical fractures, subluxations and dislocations are the result of film misinterpretation, the most frequent cause of overlooked injury is an inadequate film series.14,15

In addition to the views listed above, some authors suggest adding two lateral oblique views.16,17 Others would obtain these views only if there is a question of a fracture on the other three films or if the films are inadequate because the cervicothoracic junction is not visualized.18 The decision to take oblique views is best made by the clinician and the radiologist who will be reviewing the films.

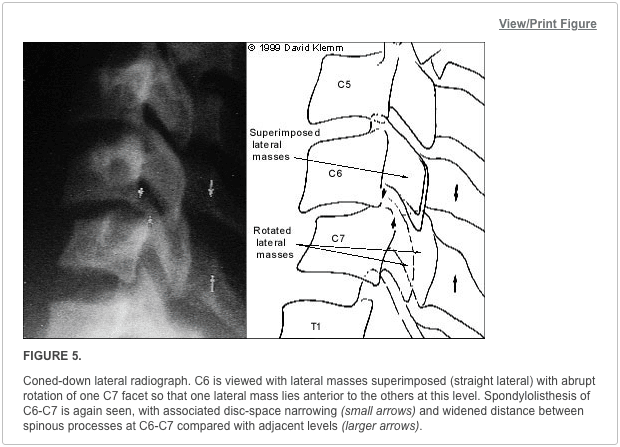

Besides identifying fractures, plain radiographs can also be useful in identifying ligamentous injuries. These injuries frequently present as a malalignment of the cervical vertebrae on lateral views. Unfortunately, not all ligamentous injuries are obvious. If there is a question of ligamentous injury (focal neck pain and minimal malalignment of the lateral cervical x-ray [meeting the criteria in Table 2]) and the cervical films show no evidence of instability or fracture, flexion-extension views should be obtained.17,19 These radiographs should only be obtained in conscious patients who are able to cooperate. Only active motion should be allowed, with the patient limiting the motion of the neck based on the occurrence of pain. Under no circumstance should cervical spine flexion and extension be forced, since force may result in cord injury.

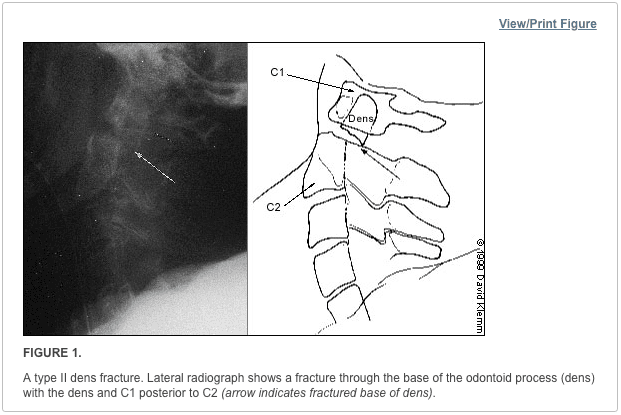

Although they may be considered adequate to rule out a fracture, cervical spine radiographs have limitations. Up to 20 percent11,20,21 of fractures are missed on plain radiographs. If there is any question of an abnormality on the plain radiograph or if the patient has neck pain that seems to be disproportionate to the findings on plain films, a CT scan of the area in question should be obtained. The CT is excellent for identifying fractures, but its ability to show ligamentous injuries is limited.22 Occasionally, plain film tomography may be in order if there is a concern about a type II dens fracture (Figure 1).

While some studies have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as an adjunct to plain films and CT scanning,23,24 the lack of wide availability and the relatively prolonged time required for MRI scanning limits its usefulness in the acute setting. Another constraint is that resuscitation equipment with metal parts may not be able to function properly within the magnetic field generated by the MRI.

Cervical Spine Radiography

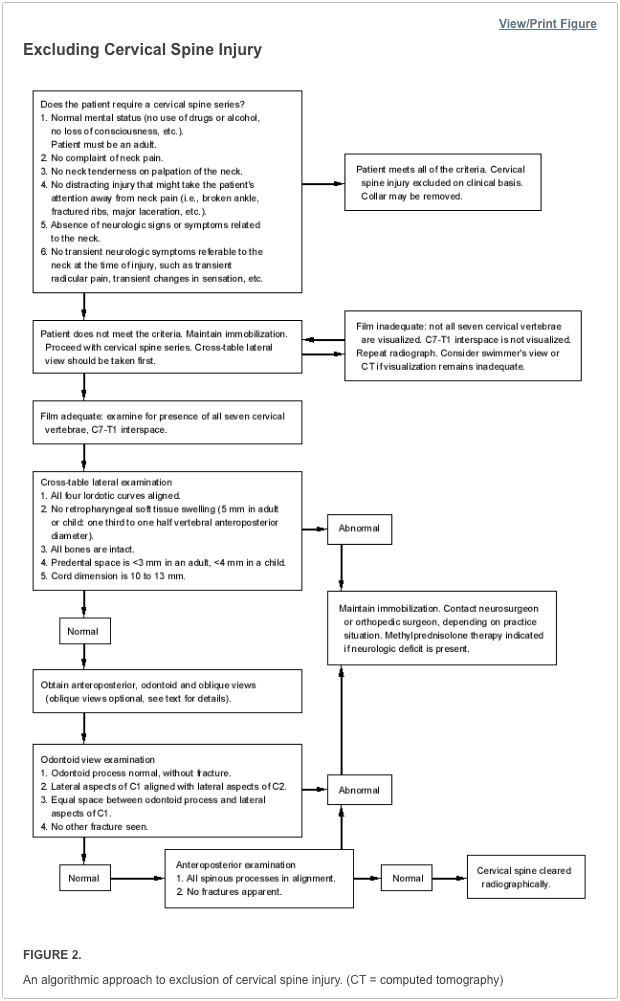

Figure 2 summarizes the approach to reading cervical spine radiographs.

Lateral View

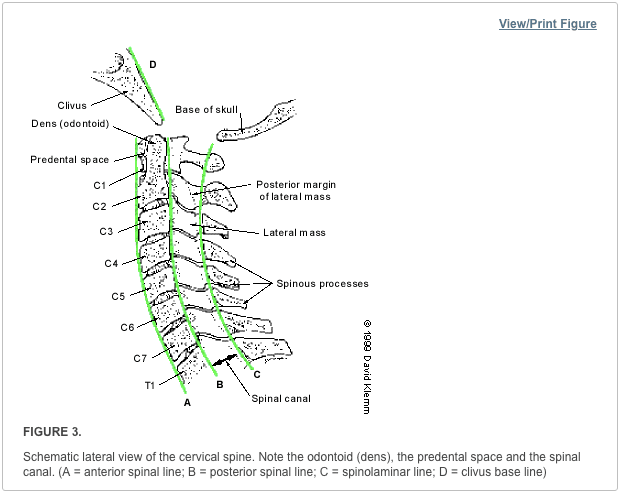

Alignment of the vertebrae on the lateral film is the first aspect to note (Figure 3). The anterior margin of the vertebral bodies, the posterior margin of the vertebral bodies, the

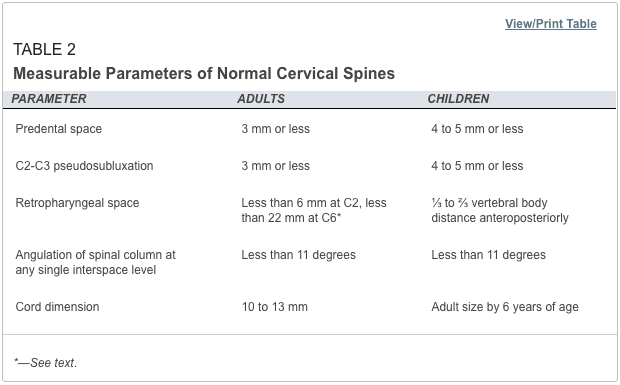

Confusion can sometimes result from pseudosubluxation, a physiologic misalignment that is due to ligamentous laxity, which can occur at the C2-C3 level and, less commonly, at the C3-C4 level. While pseudosubluxation usually occurs in children, it also may occur in adults. If the degree of subluxation is within the normal limits listed in Table 2 and the neck is not tender at that level, flexion-extension views may clarify the situation. Pseudosubluxation should disappear with an extension view. However, flexion-extension views should not be obtained until the entire cervical spine is otherwise cleared radiographically.

After ensuring that the alignment is correct, the spinous processes are examined to be sure that there is no widening of the space between them. If widening is present, a ligamentous injury or fracture should be considered. In addition, if angulation is more than 11 degrees at any level of the cervical spine, a ligamentous injury or fracture should be assumed. The spinal canal (Figure 2) should be more than 13 mm wide on the lateral view. Anything less than this suggests that spinal cord compromise may be impending.

Next, the predental space—the space between the odontoid process and the anterior portion of the ring of C1 (Figure 2)—is examined. This space should be less than 3 mm in adults and less than 4 mm in children (Table 2). An increase in this space is presumptive evidence of a fracture of C1 or of the odontoid process, although it may also represent ligamentous injury at this level. If a fracture is not found on plain radiographs, a CT scan should be obtained for further investigation. The bony structures of the neck should be examined, with particular attention to the vertebral bodies and spinous processes.

The retropharyngeal space (Figure 2) is now examined. The classic advice is that an enlarged retropharyngeal space (Table 2) indicates a spinous fracture. However, the normal and abnormal ranges overlap significantly.25 Retropharyngeal soft tissue swelling (more than 6 mm at C2, more than 22 mm at C6) is highly specific for a fracture but is not very sensitive.26 Soft tissue swelling in symptomatic patients should be considered an indication for further radiographic evaluation. Finally, the craniocervical relationship is checked.

Odontoid View

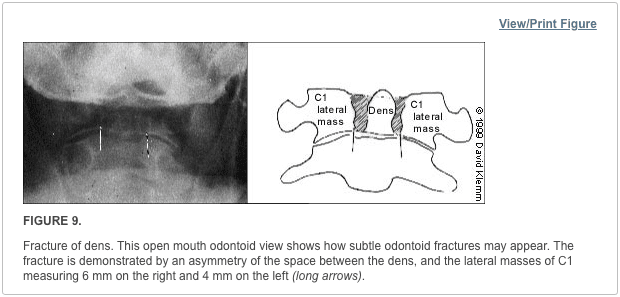

The dens is next examined for fractures. Artifacts may give the appearance of a fracture (either longitudinal or horizontal) through the dens. These artifacts are often radiographic lines caused by the teeth overlying the dens. However, fractures of the dens are unlikely to be longitudinally oriented. If there is any question of a fracture, the view should be repeated to try to get the teeth out of the field. If it is not possible to exclude a fracture of the dens, thin-section CT scans or plain film tomography is indicated.

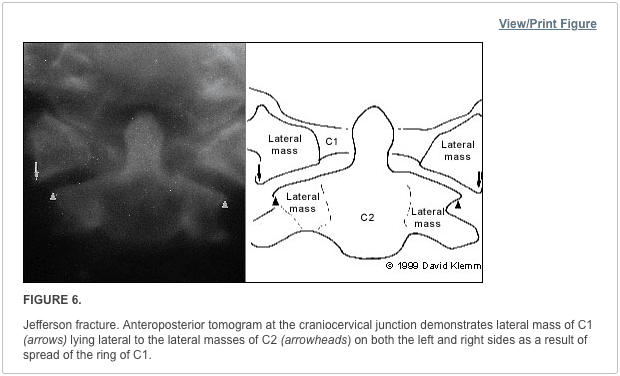

Next, the lateral aspects of C1 are examined. These aspects should be symmetric, with an equal amount of space on each side of the dens. Any asymmetry is suggestive of a fracture. Finally, the lateral aspects of C1 should line up with the lateral aspects of C2. If they do not line up, there may be a fracture of C1. Figure 6 demonstrates asymmetry in the space between the dens and C1, as well as displacement of the lateral aspects of C1 laterally.

Anteroposterior View

The height of the cervical spines should be approximately equal on the anteroposterior view. The spinous processes should be in

Common Cervical Abnormalities

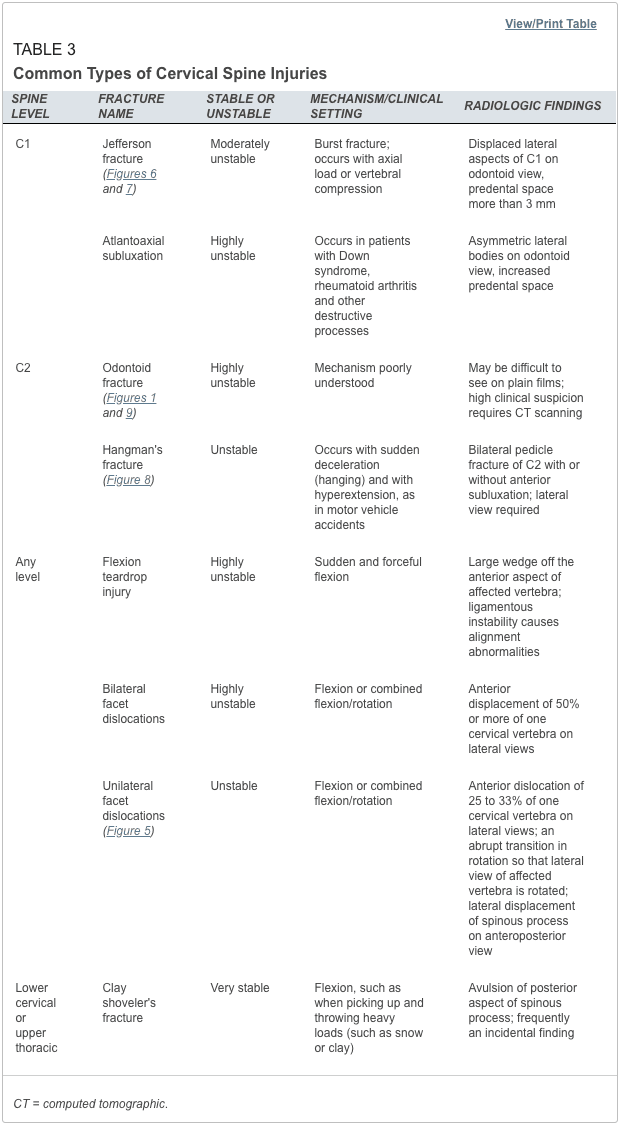

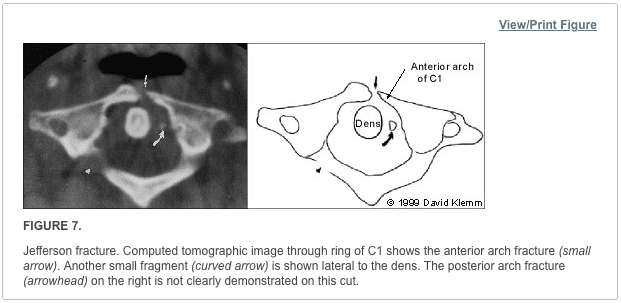

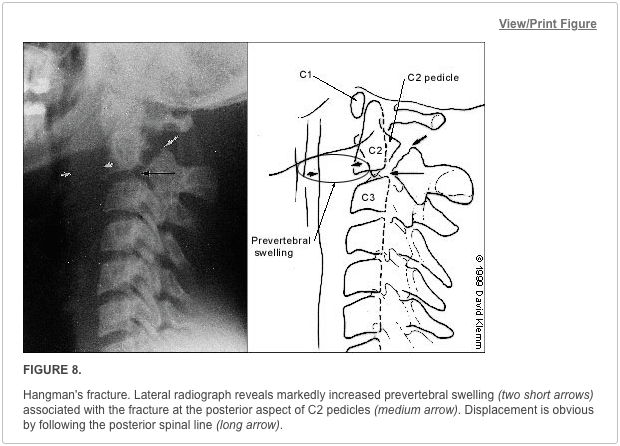

The most common types of cervical abnormalities and their radiographic findings are listed in Table 3. Except for the clay shoveler’s fracture, they should be assumed to be unstable and warrant continued immobilization until definitive therapy can be arranged. Any patient found to have one spinal fracture should have an entire spine series, including views of the cervical spine, the thoracic spine and the lumbosacral spine. The incidence of noncontiguous spine fractures ranges up to 17 percent.27,28 Figures 7 through 9 demonstrate aspects of common cervical spine fractures.

Initial Treatment of Cervical Spine and Cord

If a cervical fracture or dislocation is found, orthopedic or neurosurgical consultation should be obtained immediately. Any patient with a spinal cord injury should begin therapy with methylprednisolone within the first eight hours after the injury, with

‘Sciwora’ Syndrome: Unique in Children

A special situation involving children deserves mention. In children, it is not uncommon for a spinal cord injury to show no radiographic abnormalities. This situation has been named “SCIWORA” (spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality) syndrome. SCIWORA syndrome occurs when the elastic ligaments of a child’s neck stretch during trauma. As a result, the spinal cord also undergoes stretching, leading to neuronal injury or, in some cases,

It is important to inform the parents of young patients with neck trauma about this possibility so that they will be alert for any developing symptoms or signs. Fortunately, most children with SCIWORA syndrome have a complete recovery, especially if the onset is delayed.33 It is possible to evaluate these injuries with MRI, which will show the abnormality and help determine the prognosis: a patient with complete cord transection is unlikely to recover.3

The treatment of SCIWORA syndrome has not been well studied. However, the general consensus is that steroid therapy should be used.34 In addition, any child who has sustained a significant degree of trauma but has recovered completely should be restricted from physical activities for several weeks.34

Cervical spine radiographs include three standard views, such as the coned odontoid peg view, the anteroposterior view of the entire cervical spine, and the lateral view of the entire cervical spine. Most qualified and experienced healthcare professionals, including chiropractors, offer additional views to visualize the cervicothoracic junction as well as to evaluate the proper alignment of the spine in all patients.

Dr. Alex Jimenez D.C., C.C.S.T.

About the Authors

MARK A. GRABER, M.D., is associate professor of clinical family medicine and surgery (emergency medicine) at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City. He received his medical degree from Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, and served a residency in family medicine at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City.

MARY KATHOL, M.D., is associate professor of radiology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. She is also head of the musculoskeletal radiology section. She received her medical degree from the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kan., and served a residency in radiology at the University of Iowa College of Medicine.

Address correspondence to Mark A. Graber, M.D., Department of Family Medicine, Steindler Bldg., University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa 52242. Reprints are not available from the authors.

In conclusion, it is essential to evaluate all views of the cervical spine through imaging diagnostic assessments. While cervical spine radiographs can reveal injuries and conditions, not all neck injuries are detected through radiography. Computed tomography, or CT, scans of the cervical

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

1. Kreipke DL, Gillespie KR, McCarthy MC, Mail JT, Lappas JC, Broadie TA. Reliability of indications for cervical spine films in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1989;29:1438–9.

2. Ringenberg BJ, Fisher AK, Urdaneta LF, Midthun MA. Rational ordering of cervical spine radiographs following trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:792–6.

3. Bachulis BL, Long WB, Hynes GD, Johnson MC. Clinical indications for cervical spine radiographs in the traumatized patient. Am J Surg. 1987;153:473–8.

4. Hoffman JR, Schriger DL, Mower W, Luo JS, Zucker M. Low-risk criteria for cervical-spine radiography in blunt trauma: a prospective study. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1454–60.

5. Saddison D, Vanek VW, Racanelli JL. Clinical indications for cervical spine radiographs in alert trauma patients. Am Surg. 1991;57:366–9.

6. Kathol MH, El-Khoury GY. Diagnostic imaging of cervical spine injuries. Seminars in Spine Surgery. 1996;8(1):2–18.

7. Lally KP, Senac M, Hardin WD Jr, Haftel A, Kaehler M, Mahour GH. Utility of the cervical spine radiograph in pediatric trauma. Am J Surg. 1989;158:540–1.

8. Rachesky I, Boyce WT, Duncan B, Bjelland J, Sibley B. Clinical prediction of cervical spine injuries in children. Radiographic abnormalities. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:199–201.

9. Laham JL, Cotcamp DH, Gibbons PA, Kahana MD, Crone KR. Isolated head injuries versus multiple trauma in pediatric patients: do the same indications for cervical spine evaluation apply? Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21:221–6.

10. McKee TR, Tinkoff G, Rhodes M. Asymptomatic occult cervical spine fracture: case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1990;30:623–6.

11. Woodring JH, Lee C. Limitations of cervical radiography in the evaluation of acute cervical trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34:32–9.

12. Spain DA, Trooskin SZ, Flancbaum L, Boyarsky AH, Nosher JL. The adequacy and cost effectiveness of routine resuscitation-area cervical-spine radiographs. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:276–8.

13. Tintinalli JE, Ruiz E, Krome RL, ed. Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

14. Gerrelts BD, Petersen EU, Mabry J, Petersen SR. Delayed diagnosis of cervical spine injuries. J Trauma. 1991;31:1622–6.

15. Davis JW, Phreaner DL, Hoyt DB, Mackersie RC. The etiology of missed cervical spine injuries. J Trauma. 1993;34:342–6.

16. Apple JS, Kirks DR, Merten DF, Martinez S. Cervical spine fractures and dislocations in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1987;17:45–9.

17. Turetsky DB, Vines FS, Clayman DA, Northup HM. Technique and use of supine oblique views in acute cervical spine trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:685–9.

18. Freemyer B, Knopp R, Piche J, Wales L, Williams J. Comparison of five-view and three-view cervical spine series in the evaluation of patients with cervical trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:818–21.

19. Lewis LM, Docherty M, Ruoff BE, Fortney JP, Keltner RA Jr, Britton P. Flexion-extension views in the evaluation of cervical-spine injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:117–21.

20. Mace SE. Emergency evaluation of cervical spine injuries: CT versus plain radiographs. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:973–5.

21. Kirshenbaum KJ, Nadimpalli SR, Fantus R, Cavallino RP. Unsuspected upper cervical spine fractures associated with significant head trauma: role of CT. J Emerg Med. 1990;8:183–98.

22. Woodring JH, Lee C. The role and limitations of computed tomographic scanning in the evaluation of cervical trauma. J Trauma. 1992;33:698–708.

23. Schaefer DM, Flanders A, Northrup BE, Doan HT, Osterholm JL. Magnetic resonance imaging of acute cervical spine trauma. Correlation with severity of neurologic injury. Spine. 1989;14:1090–5.

24. Levitt MA, Flanders AE. Diagnostic capabilities of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in acute cervical spinal column injury. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:131–5.

25. Templeton PA, Young JW, Mirvis SE, Buddemeyer EU. The value of retropharyngeal soft tissue measurements in trauma of the adult cervical spine. Cervical spine soft tissue measurements. Skeletal Radiol. 1987;16:98–104.

26. DeBehnke DJ, Havel CJ. Utility of prevertebral soft tissue measurements in identifying patients with cervical spine fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:1119–24.

27. Powell JN, Waddell JP, Tucker WS, Transfeldt EE. Multiple-level noncontiguous spinal fractures. J Trauma. 1989;29:1146–50.

28. Keenen TL, Antony J, Benson DR. Non-contiguous spinal fractures. J Trauma. 1990;30:489–91.

29. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF Jr, Holford TR, Baskin DS, Eisenberg HM, et al. Methylprednisolone or naloxone treatment after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow-up data. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:23–31.

30. Galandiuk S, Raque G, Appel S, Polk HC Jr. The two-edged sword of large-dose steroids for spinal cord trauma. Ann Surg. 1993;218:419–25.

31. Grabb PA, Pang D. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality in children. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:406–14.

32. Pang D, Pollack IF. Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality in children—the SCIWORA syndrome. J Trauma. 1989;29:654–64.

33. Hadley MN, Zabramski JM, Browner CM, Rekate H, Sonntag VK. Pediatric spinal trauma. Review of 122 cases of spinal cord and vertebral column injuries. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:18–24.

34. Kriss VM, Kriss TC. SCIWORA (spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality) in infants and children. Clin Pediatr. 1996;35:119–24.

The editors of AFP welcome the submission of manuscripts for the Radiologic Decision-Making series. Send submissions to Jay Siwek, M.D., following the guidelines provided in “Information for Authors.”

Coordinators of this series are Thomas J. Barloon, M.D., associate professor of radiology and George R. Bergus, M.D., assistant professor of family practice, both at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City.

Additional Topics: Acute Back Pain

Back pain is one of the most prevalent causes of disability and missed days at work worldwide. Back pain attributes to the second most common reason for doctor office visits, outnumbered only by upper-respiratory infections. Approximately 80 percent of the population will experience back pain at least once throughout their life. The spine is a complex structure made up of bones, joints, ligaments, and muscles, among other soft tissues. Because of this, injuries and/or aggravated conditions, such as herniated discs, can eventually lead to symptoms of back pain. Sports injuries or automobile accident injuries are often the most frequent cause of back pain, however, sometimes the simplest of movements can have painful results. Fortunately, alternative treatment options, such as chiropractic care, can help ease back pain through the use of spinal adjustments and manual manipulations, ultimately improving pain relief.

EXTRA EXTRA | IMPORTANT TOPIC: Chiropractic Neck Pain Treatment

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: coach@elpasofunctionalmedicine.com

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card